The life and work of Maurice Ravel

- The sound of Experiment

- Oct 21, 2024

- 11 min read

Early life

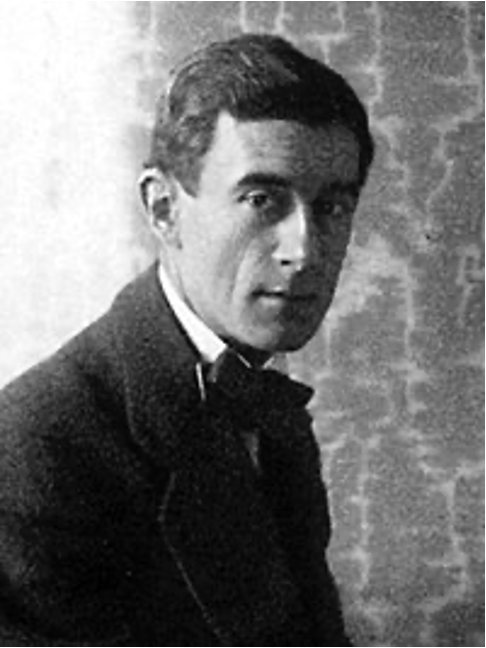

Joseph Maurice Ravel was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He was born on March 7, 1875 and died on December 28, 1937. He began piano lessons when he was seven years old. Five years later, he began studying harmony, counterpoint and composition. It was during this period that the composer wrote his first known compositions. Although he was not a child prodigy, He had a special musical talent. His teacher found that Ravel's perception of music was natural to him "and not, as in the case of so many others, the result of effort" [1].

In 1888, Ravel met the young pianist Ricardo Viñez, who became not only a lifelong friend, but also one of the most important interpreters of his works and an important link between Ravel and Spanish music. The two shared an appreciation for Wagner, Russian music, and the writings of Poe, Baudelaire, and Malarmé. At the Universelle Exhibition in Paris in 1889, Ravel was very impressed by the new Russian works. This music had a lasting influence on both Ravel and his older contemporary Claude Debussy, as did the exotic sound of the Javanese gamelan, also heard during the Exhibition [1]

In the same year, he began his studies at France's most important music college, the Conservatoire de Paris. In 1891, Ravel won first prize at the Conservatory's piano competition, but otherwise did not stand out as a student. He made steady, unspectacular progress, but, in the words of musicologist Barbara Kelly, "he was instructive only on his own terms." His later teacher Gabriel Fauré understood this, but it was not generally accepted by the conservative school of the Conservatory of the 1890s. Ravel was expelled in 1895, without having won any other prizes [1].

Ravel was never as diligent a piano student as his colleagues. It was clear that as a pianist he would never reach them and therefore he focused on composition [1]. Around this time, Joseph Ravel introduced his son to Eric Satie, who was earning a living as a café pianist. He was one of the first musicians, along with Debussy, to recognize Satie's originality and talent. Satie's constant experimentation in musical form inspired Ravel, who counted them "priceless" [1].

Later, Ravel was readmitted to the Conservatory and studied composition with Fauré and took private lessons in counterpoint with André Gödaltz. Both of these teachers, especially Fauré, considered him special and were key influences on his development as a composer. Ravel's position at the Conservatory was however undermined by the hostility of the Director, who deplored the young man's musically and politically progressive outlook. Consequently, he was "a marked man, against whom all weapons were good." He wrote some important works while studying with Fauré, but did not win prizes and was therefore expelled again in 1900. Pierre Lalo, a music critic, believed that Ravel showed talent, but he was heavily indebted to Debussy and should imitate Beethoven instead. In the following decades, Lalo became Ravel's most implacable critic.

Around 1900 Ravel and a number of innovative young artists, poets, critics and musicians formed an informal group. They became known as "The Hooligans", a name coined by Vinez to represent their status as "artistic outcasts". They met regularly until the start of the First World War, and members encouraged each other with intellectual arguments and representations of their works. The members of the group were constantly changing and at various times included Igor Stravinsky and Manuel de Falla as well as their French friends.

Among the enthusiasms of the "Hooligan" was the music of Debussy. Ravel had already known Debussy since the 1890s and their friendship continued for more than ten years. A few years later, André Scheiner conducted the premiere of Debussy's opera "Pelléas and Mélisade" at the Opéra-Comic, which divided musical opinion. Dubois explicitly forbade the students of the Conservatory to attend, and the conductor's friend and former teacher Camille Saint-Saëns was among those who loathed the work. The "Hooligans" supported the project vigorously. The first performance of the opera had fourteen performances and Ravel attended them all [1].

From the beginning of his career, Ravel appeared indifferent to praise or criticism. Those who knew him well believed that this was not a lie but absolutely genuine. The only aspect of his music that he really appreciated was his own. He was a perfectionist and strict with himself. By age twenty he was, "selfish, a little arrogant, intellectually biased, given to gentle teasing." He dressed like a dandy and was meticulous about his appearance and behavior. Some comment that Ravel had the "appearance of a well-dressed jockey", whose large head seemed to fit suitably with his formidable intellect [1].

During the early years of the new century, Ravel made five attempts to win France's most prestigious prize for young composers, the Rome Prize, whose previous winners included Berlioz, Gounot, Bizet, Massenet and Debussy. In 1900, Ravel was eliminated in the first round. In 1901 he won second prize for the competition. In 1902 and 1903 he won nothing: according to musicologist Paul Landormi, the judges suspected Ravel of fooling them by submitting cantatas so academic that they ended up resembling parodies. In 1905 Ravel entered the contest for the last time and unwittingly caused an uproar. He was eliminated in the first round, which even critics who disliked his music, including Lalo, denounced as unjustified. Press outrage grew when it was revealed that the senior professor at the Conservatory was a member of the jury and that only his students were selected in the final round. His insistence that this was pure coincidence was not well received. The Ravel affair became a national scandal and led Dubois to early retirement, who was replaced by Fauré, appointed by the government to carry out a radical reorganization of the Conservatory [1].

Career

Alongside the music he composed, Ravel gave lessons to some young musicians who he felt could benefit from them. The best-known composer who studied with Ravel was Ralph Vaughan Williams, who was his student for three months. Vaughn Williams' memories shed little light on Ravel's private life, about which the latter's restrained and secretive personality has led to much speculation. Vaughan Williams, Rosenthal, and Marguerite Long have all recorded that Ravel frequented brothels. Long attributed this to his self-consciousness about his small stature and subsequent lack of trust in women. According to other accounts, none of them firsthand, Ravel was in love with Misia Edwards, or wanted to marry violinist Hélène Jourdan-Morange. Rosenthal records and rejects modern speculation that Ravel, a lifelong bachelor, may have been gay. Such speculations were repeated in a life of Ravel in 2000 by Benjamin Ivry. Later studies concluded that Ravel's sexuality and personal life remain a mystery. Ravel's first concert outside France was in 1909 [1].

In 1914, when Germany invaded France, Ravel tried to join the French Air Force. He considered his small stature and light weight ideal for an aviator, but was rejected due to his age and a minor heart problem. While waiting to be drafted, he dedicated the three songs to people who could help him enlist. After several unsuccessful attempts to enlist, Ravel finally joined the Thirteenth Artillery Regiment as a truck driver in March 1915, when he was forty years old. Stravinsky expressed his admiration for his friend's courage. Some of Ravel's duties put him in mortal danger, driving ammunition at night under heavy German bombardment. At the same time, his peace was undermined by his mother's failing health. His own health also deteriorated. He suffered from insomnia and digestive problems and underwent bowel surgery [1].

1. Music

Musically, Ravel drew on many generations of French composers, from Cuperin and Rameau to Fauré and the most recent innovations of Satie and Debussy. Foreign influences include Mozart, Schubert, Liszt, and Chopin. He considered himself in many ways a classicist, often using traditional structures and forms, such as the tripartite, to present his new melodic and rhythmic content and innovative harmonies. He attached great importance to melody, telling Vaughan Williams that there is "an implicit melodic outline to all vital music." His themes are often tropical instead of using the familiar large or minor scales [1].

Ravel liked the dance forms, most famously the bolero and the pavana, but also the minuet, forlane, rigaunton, waltz, charda, habanera and pasacaglia. National and regional consciousness was important to him, and although a planned concerto on Basque themes never materialized, his works include allusions to Hebrew, Greek, Hungarian and Gypsy themes. He wrote several short pieces paying homage to composers he admired – Borodin, Chabrier, Fauré and Haydn, interpreting their features in a ravel style. Another major influence was literary rather than musical: Ravel said he learned from Poe that "true art is a perfect balance between pure intellect and emotion," with the consequence that a piece of music must be a perfectly balanced entity without irrelevant material allowed to creep in.

Many music lovers began to apply the term impressionism to Debussy and Ravel, and the works of the two composers were often taken as part of a single genre. Ravel believed that Debussy was indeed an impressionist, but that he was not. Orenstein comments that Debussy was more spontaneous and relaxed in his composition, while Ravel was more careful in form and virtuosity. Ravel wrote that Debussy was obviously a genius, creating his own musical rules, constantly evolving and expressing himself freely, but always remaining faithful to French tradition [1].

The two composers ceased to be friendly in the mid-1900s, for musical and possibly personal reasons. Their admirers began to form factions, with fans of one composer denigrating the other. Further, disputes arose about the chronology of composers' works and who influenced whom. Prominent in the anti-Ravel camp was Lalo, who wrote: "Where M. Debussy is all sensitivity, Ravel is all insensitivity, borrowing without hesitation not only the technique but also the sensitivity of other men." Public tension led to personal alienation. Ravel said: "It's probably better for us, after all, to be on cold terms for irrational reasons." Nichols suggests an additional reason for the rift. In 1904, Debussy abandoned his wife and went to live with singer Emma Bardak. Ravel, along with his close friend and confidant Misia Edwards and opera star Lucienne Breval, contributed a modest regular income to Lily Debussy [1].

1. Banning his music

During the war, the National Association for the Defense of French Music was formed. Among others, part of the association were Saint-Saëns and Dubois, who campaigned for a ban on the performance of contemporary German music. Ravel refused to participate, telling the union's committee: "It would be dangerous for French composers to systematically ignore the productions of their foreign colleagues and thus form a kind of national clique: our musical art, which is so rich today, would degenerate, leading it to banal formulas." Because of this, the union banned Ravel's music from its concerts [1].

Later, Ravel's mother died, which led him to a "horrible despair" and exacerbated the anguish he felt about the suffering suffered by the people of his country during the war. During the war years he composed very few works. After the war, those close to Ravel acknowledged that he had lost much of his physical and mental stamina. The production of his works became smaller. However, after Debussy's death in 1918, he was regarded both in France and abroad as the leading French composer of the time. Fauré wrote to him: "I am happier than you can imagine for the firm position which you occupy and which you have acquired so brilliantly and so quickly. It is a source of joy and pride for your old professor."

Death

In October 1932, Ravel suffered a blow to the head in a taxi accident. As early as 1927, close friends were concerned about Ravel's increasing absence, and within a year of the accident he began to show symptoms suggestive of aphasia. Before the accident he had begun working on the music for a film, Don Quixote (1933), but was unable to meet the production schedule and Jacques Hubert wrote most of the score. He didn't compose anything else after that. The exact nature of his illness is unknown. Experts have ruled out the possibility of a tumor and have suggested dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Although he was no longer able to write music or perform, Ravel remained physically and socially active until his final months. Henson notes that Ravel retained most or all of his auditory images and could still listen to music in his head.

In 1937 Ravel began to suffer pain from his condition and after examination by a well-known neurosurgeon in Paris, he underwent brain surgery and his condition seemed to improve. But his improvement was short-term and soon the composer fell into a coma and died on December 28, at the age of 62. On December 30, 1937, Ravel was buried next to his parents in a granite grave in Paris. As the composer was an atheist, there was no religious ceremony.

Compositions

Pavane pour une infante défuntte – Ravel (1899)

The first work we will hear on today's show is "Pavana for a dead Infante" performed by the Orchestre National de France under the baton of Dalia Stashevka.

Ravel wrote the work in 1899, during his studies at the Conservatory of Paris. Originally, the work was a piano solo commissioned by the Princess de Polignac [1]. Ravel himself described the work as "an invocation to the Spanish court" [9]. Although it had no impact when it was released, it was later recognized as one of the composer's greatest works [1].

String Quartet (1903)

We will continue the show musically with his work entitled "String Quartet" by the Eben Quartet. It was written in 1903.

The quartet bears superficial similarities to Debussy's string quartet, which was written ten years earlier.

The tomb of Couperin (1914-1917)

We continue with the third part of the work entitled "Le tombeau de Couperin".

It was written between 1914 and 1917. It is a suite for solo piano and is considered to be the most important of the composer's war works. The suite celebrates the tradition of François Cuperin, the 18th-century French composer. Each of the moves/parts is dedicated to one of Ravel's friends who died in the war. It is one of Ravel's ballets danced in its orchestral version at the Champs-Elysées Theatre [1].

The Spanish Hour (1911)

We will continue with the opening of the opera entitled "Spanish Time" designed by Maurice Sedak and directed by Frank Corsaro.

It is the first opera completed by Ravel. The project was completed in 1907, but the director of the Opéra-Comique repeatedly postponed its premiere. He worried that the audience of the Opéra-Comique, which included prominent mothers and daughters, would be badly received by its plot, which was their bedroom farce. The song received only partial success in its first production and only became popular in the 1920s [1].

The play is one of Ravel's works set in or depicting Spain. Nichols comments that the necessary Spanish coloring gave Ravel a reason for his virtuosic use of the modern orchestra, which the composer considered "perfectly designed to underline and exaggerate comic effects." On the other hand, some find the characters artificial and that the human element is missing from the piece. Although one-act operas are generally staged less frequently than full-length operas, Ravel's operas are regularly staged both in France and abroad [1].

Bolero (1920)

We will continue musically with the work "Bolero".

The composition of the work was completed in 1920. It is the last composition completed by the composer in that decade and his most famous. He was originally commissioned to produce a score, but since he was unable to secure the rights to orchestrate another score as he had planned, he decided "an experiment in a very particular and limited direction ... a seventeen-minute piece consisting entirely of an orchestral part without music." Ravel continued that the work was "a long, very gradual crescendo. There are no contrasts and there is almost no invention except the design and the way of execution. The issues are completely impersonal." The play was a massive success, which surprised Ravel, but not necessarily in a positive way. When a lady in the audience shouted "The madman! The madman" at the premiere, remarked: "Oh, That lady understood what I mean!" Ravel commented to Arthur Honegger, one of the Group of Six: "I have only written one masterpiece – Bolero. Unfortunately there is no music in it."

Nahandove (1925-1926)

We will close today's show with the first song from the collection "Songs of Madagascar" entitled "Nahadové"

It was written between 1925 and 1926. It is a set of three exotic songs with lyrics from the poetry collection of the same name by Évariste de Parni. The composer dedicated it to the American musician and philanthropist Elizabeth Sprang Coolidge [1, 2].

Bibliography

Comments